Testing Einstein’s theory of relativity with the clearest gravitational-wave signal yet

An international team, with key contributions from AEI researchers, identified three gravitational-wave tones in GW250114 for the first time and conducted the most stringent tests of general relativity.

To the point:

- Relativity put to the test: Relativity put to the test: A LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA team has conducted some of the most precise tests of Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The results were published in Physical Review Letters today.

- Einstein holds fast: In all tests, the observations match the theory’s predictions. In some cases, the tests based on this signal alone are two to three times more stringent than those obtained by combining data from dozens of other signals.

- The clearest signal: The team used data from GW250114, the strongest gravitational-wave signal ever detected from the merger of two black holes.

- Like a bell: For the first time, detailed analyses of the complete signal and the ringdown phase, which occurs shortly after the merger, have identified or constrained three gravitational-wave tones.

Relativity put to the test

A year ago, almost to the day, the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA collaboration observed by far the clearest gravitational-wave signal seen to date. GW250114 came from a coalescence of black holes with masses between 30 to 40 times that of our Sun about 1.3 billion light-years away.

“This signal has already proven to be a great boon for a test of the nature of black holes and of Hawking’s area law,” says Alessandra Buonanno, director of the Astrophysical and Cosmological Relativity department at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics (Albert Einstein Institute, AEI) in the Potsdam Science Park. “Now we have gone one step further and published some of the most stringent limits on deviations from Einstein’s theory of general relativity using GW250114.”

Additional analysis of the GW250114 data was published today in Physical Review Letters. The writing team included several AEI members: Alessandra Buonanno, who served as chair, and Lorenzo Pompili, Elisa Maggio, and Elise Sänger, who conducted several of the analyses reported in the publication.

Because GW250114 was observed so clearly, it can be compared in much greater detail to predictions from Einstein’s theory of relativity than other signals. This makes it possible to test whether general relativity holds true in the extreme conditions of a black hole coalescence, where strong gravitational fields meet rapidly changing dynamics. Any deviations from the predictions of general relativity could hint at new physics beyond Einstein’s theory.

Like a struck bell

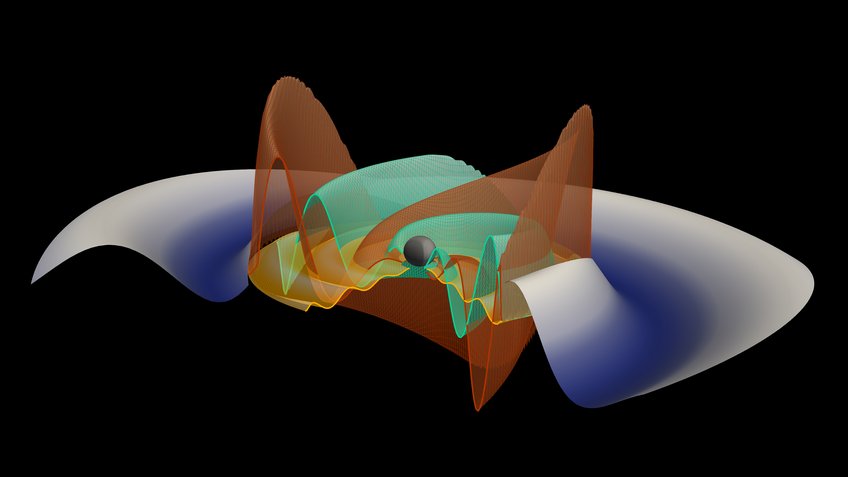

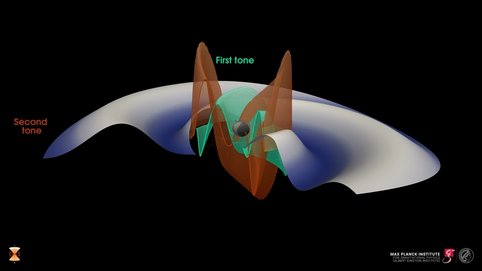

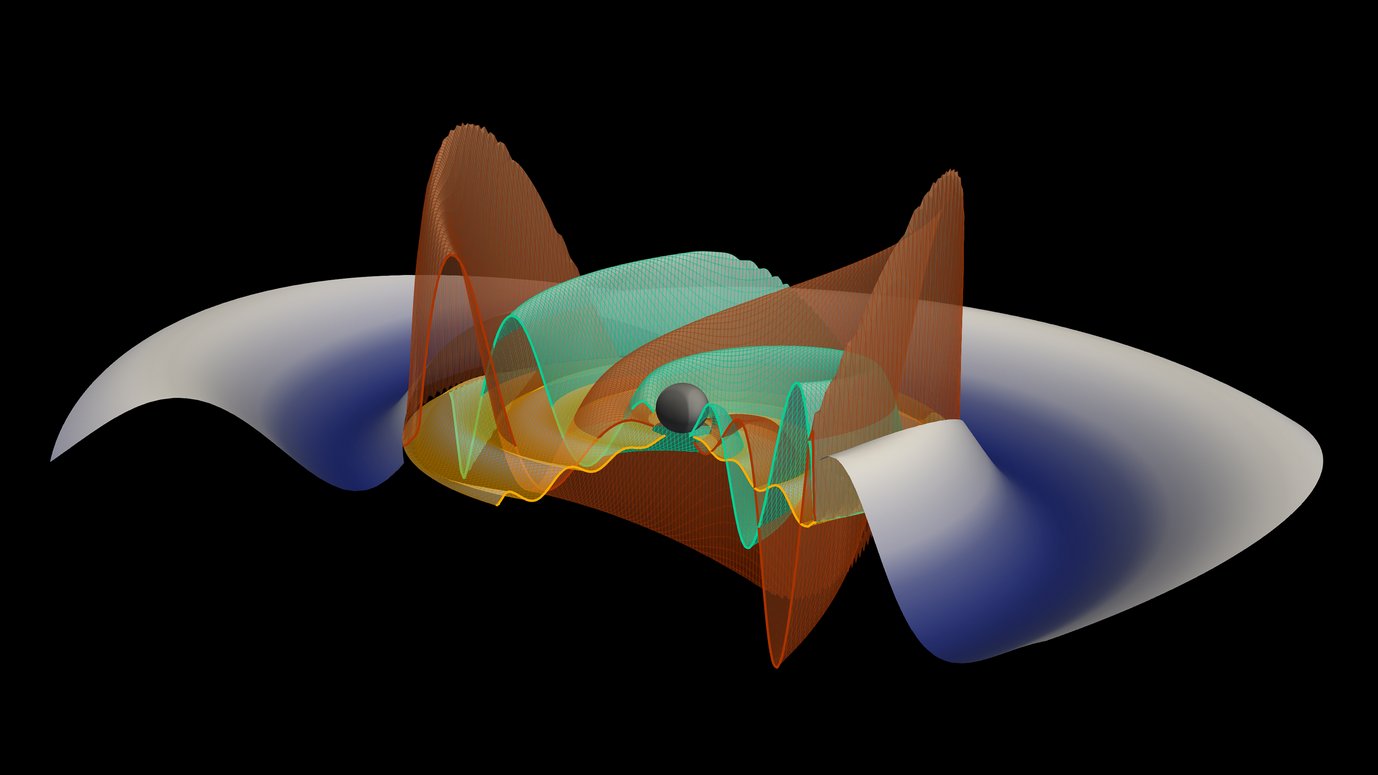

The international research team obtained some of the key results using a method known as black hole spectroscopy. For this, the team focused on the ringdown of the GW250114 signal – the phase when the black hole settles into its final state right after the merger – and the characteristic spectrum of gravitational-wave modes, or tones, emitted during this phase. These tones resemble the sounds a bell makes when struck: Each tone is described by two numbers: its frequency and the rate at which it is fading. Measuring the spectrum of the tones and their fading times is called black hole spectroscopy.

According to general relativity, every black hole can be fully described by its mass and angular momentum (spin). This is also called the “no-hair theorem”. Mass and spin must therefore completely determine the frequency and fading rate of each gravitational-wave tone in the ringdown. Thus, characterizing multiple gravitational-wave tones enables a unique and powerful test of general relativity and a search for new physics beyond Einstein’s theory.

“By observing the ringdown alone, we tested whether the remnant behaved like a rotating black hole in Einstein’s theory of gravity,” says Lorenzo Pompili, a former PhD student in the Astrophysical and Cosmological Relativity Department. “By analyzing data from only the ringdown phase, we identified the fundamental gravitational-wave tone and its faster-fading first overtone. We confirmed that their frequencies and fading times match those predicted by general relativity.”

For the first time, a triad of gravitational-wave tones

For the first time, researchers at the AEI in Potsdam found a third tone in the signal’s ringdown phase using a new data analysis tool they developed.

“Our analysis tool, originally proposed in 2018, takes into account the complete black-hole coalescence and makes no prior assumptions about the tones emitted during the ringdown phase,” explains Elisa Maggio, a former Marie Curie Fellow in the Astrophysical and Cosmological Relativity department and now an INFN Researcher in Rome, Italy. Maggio and Pompili collaborated on developing the most recent version of the tool and conducting the analysis. “By incorporating information from the entire signal, we constrained a higher-pitched tone at approximately twice the fundamental frequency for the first time, once again matching theoretical predictions.”

Together, the two tests – one looking at the ringdown alone and the other considering the full signal – complement each other. Once again, they empirically vindicate the rotating black hole solution discovered in 1963 by Roy Kerr.

One signal beats dozens of others

The research team also examined an earlier phase of the clearly observed black hole coalescence when the two black holes were orbiting each other more slowly.

“We used a flexible, theory-independent method developed earlier at the AEI to determine how much the gravitational-wave signal deviated from the predictions of general relativity early in the coalescence,” says Elise Sänger, a PhD student in the Astrophysical and Cosmological Relativity department who conducted the analysis. “Remarkably, using data from this one clearly observed signal alone allows us to set some of the most stringent constraints on possible deviations from general relativity.”

The constraints derived using the AEI-developed model are two to three times more stringent than those obtained by combining data from dozens of signals in the latest fourth Gravitational-Wave Transient Catalogue (GWTC-4.0).

Only the beginning

“These results demonstrate the great scientific value of accurate waveform models and sophisticated data analysis techniques,” says Alessandra Buonanno. “But this is only the beginning. Future observing runs will allow us to detect signals like GW250114 more frequently and more clearly. Each one will open new avenues for testing Einstein’s theory and searching for new physics.”